Editor’s note: This article is part of Project Cyber, which explores and characterizes the myriad threats facing the United States and its allies in cyberspace, the information environment, and conventional and irregular spaces. Please contact us if you would like to propose an article, podcast, or event environment. We invite you to contribute to the discussion, explore the difficult questions, and help.

Risk is easily measured in meals. Vladimir Lenin claimed, “[e]very society is three meals away from chaos.” Britain’s MI5 believes society is “four meals away from anarchy.” If you can’t feed people, societal discord could follow, and where there are preexisting grievances, the problem is even more acute.

For foreign influence operations, food insecurity offers a ready lever for targeting communities at their most vulnerable. It’s easy to manipulate hungry people. And when that insecurity comes from a natural disaster, the influence operational environment becomes quite fertile. Victims look for hope, which leaves an open door for foreign influence. The problem has already taken hold and is poised to grow. But the solution already exists—right under our noses—money.

It’s tough to target hungry people when victims are fed. To put food back on the table, vulnerable states could turn to parametric insurance, a risk-transfer format already used by some developing market nations for hurricane and earthquake protection.

https://irregularwarfareinsider.podbean.com/e/money-talks-and-hunger-walks-buying-down-state-actor-influence-risk/Parametric insurance not only provides pre-negotiated relief capital but also requires a much smaller up-front capital commitment, allowing donor states to achieve considerable leverage when providing support, particularly by engaging the private insurance market.

By developing a mechanism for providing cover to vulnerable states or quasi-state entities capable of dispensing claim payments, the United States could use a purely humanitarian approach to economic and food security to deny access to state influence peddlers. This solution is easy to implement, has precedent in the global south, is inexpensive, and can scale.

Influence Operations in Context

An oft-cited 2009 RAND report defines influence operations as “the coordinated, integrated, and synchronized application of national diplomatic, informational, military, economic, and other capabilities in peacetime, crisis, conflict, and post-conflict to foster attitudes, behaviors, or decisions by foreign target audiences.” The report further qualifies operations as in “furtherance of US interests and objectives.” Still, the model is portable across borders and has been around at least since a “smear campaign” was run against Marc Antony in 445 B.C.E. However, with more than 17 billion devices and more than 5 billion people connecting to the internet, it’s hard to ignore the scale that influence operations can achieve today.

The effects of state-actor influence operations are notoriously difficult to quantify. Operations may seek to make some portions of the population feel marginalized or neglected. Only a few campaign attempts need to be successful, which means that a state willing to kiss a lot of toads, so to speak, can work its way to occasionally powerful results at a relatively low cost. Meanwhile, the potential cadence of the threat makes “responding to malicious influence campaigns solely in a reactive manner [is] insufficient to stem the tide,” according to Malzac.

This is particularly true of influence operations following natural disasters. Natural disasters are clearly on the rise, and this increase in frequency only means that disaster disinformation and influence will become more common—and presumably more effective. One of the underlying drivers, climate change, has itself become a rich foreign influence topic.

The rise of influence efforts was immediately evident following the February 2023 Kahramanmaras, Türkiye, earthquake, with accusations of US “tectonic” and “seismic” weapons use. For the wildfires in Hawaii that same year, allegations focused on the use of a “directed energy weapon.” Post-disaster foreign influence operations are most effective when targeting vulnerable populations with preexisting grievances. Most recently, disinformation circulated after Hurricanes Helene and Milton devastated portions of the Southeast, with rumors that the US government used weather technology to create the hurricanes, deliberately targeting Republican voters. A population at odds with its government may readily accept disinformation and other forms of influence simply because they’re being told what they want to hear.

While the problem looks thorny, the solution may be straightforward and have a track record spanning three decades.

Parametric Insurance 101

Think about an insurance policy that pays out strictly on the magnitude of an event, like a Category 5 hurricane or a 7.0Mw earthquake. If that magnitude is reached, the insurer pays. That’s parametric insurance. Parametric insurance has become particularly effective in developing markets, with regular use in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. It’s also used in more mature economies to fill holes in the traditional insurance market.

To understand how parametric insurance works, consider earthquake risk insurance in Istanbul and the nearby Marmara Sea (a common region for parametric insurance). The area covered would be defined by coordinates, creating a “box” in which the earthquake’s epicenter would have to occur for the policy to trigger. The policy would also specify the magnitude of the quake necessary—for Istanbul earthquakes, common levels range from 6.5-7.5Mw, as measured by the US Geological Survey. What results is effectively a checklist, and when the conditions on that checklist are satisfied, the policy pays out.

Although parametric insurance is standard in the private market, governments have also become frequent users. Jamaica, Mexico, and Chile are among the states that have purchased parametric insurance, along with a range of government catastrophe programs across Africa. They seek parametric protection because it is straightforward (as above), relies on a third-party data source for triggering that makes it resistant to manipulation and dispute, and pays quickly.

Unlike foreign aid, parametric insurance allows donor states to scale their capital commitments. In addition to being cost-effective, because it’s negotiated ahead of need, parametric programs require that the donor state (or the benefitting state, if it pays for its protection) only pay the policy premium rather than the complete aid package. Imagine having $100 million in effect for only $5-10 million in outlay. If $100 million were necessary due to a triggering event, it would come from a private sector that is sufficiently resourced to pay that amount. After all, insurers paid nearly $100 billion in 2023 for natural disaster events.

Parametric insurance isn’t new, but using it to counter foreign influence would be. Recent droughts in Moldova show how this could work.

Finding a Laboratory

Moldova struggles with disinformation and influence operations, drought, and economic security, making it a compelling test case for parametric insurance as a counter-influence tool. Agriculture is responsible for 12% of Moldova’s gross domestic product (GDP), 27% of the labor force, and 75% of its physical territory. In Gagauzia, a semi-autonomous region that has strained relations with Moldova’s official government, agriculture’s contribution of $125 million (2.2 billion Moldovan leu) represents 72% of the region’s GDP. If its agriculture business is threatened, Gagauzia suffers profoundly, as is the case for the rest of Moldova.

Unfortunately, this economic and food security problem comes within a society with competing loyalties. While Moldova seeks to align with the European Union, its two semi-autonomous regions, Gagauzia and Transnistria, look east to Moscow due to a combination of animosity toward the Moldovan-Romanian majority and a healthy dose of Russo-nostalgia. This has led to a fertile ground for influence operations, where the Gagauz are more than happy to receive sympathetic messaging as a show of support rather than a disruptive force.

The tenuous (at best) balance among competing interests in Moldova was challenged in 2022 by a severe drought—a risk the country has historically faced and can expect to intensify in the future. The drought caused the country’s agricultural sector to shrink by 18% in a year when energy security and the war in Ukraine had already imperiled the economy of one of Europe’s poorest countries. That year, the drought in Gagauzia was paired with foreign influence operations. Tapping into the drought’s effect on the local economy and the preexisting grievances that help disaster disinformation find purchase, Moldova was bombarded with foreign influence, largely welcomed by the Gagauz. Messaging on the drought was intensified with further influence on energy and economic woes, not to mention encouragement to protest.

The role of Russian influence in Moldova is part of a much broader and more intricate relationship dating back to the Soviet Union. However, there are clear cases of influence operations related directly to prevailing economic concerns, and the drought’s impact on the agriculture sector is among them. Again, there is no single solution to fending off foreign influence, but it seems as though the drought problem is calling for an economic security solution—a simple one.

Parametric insurance could do some heavy lifting in Gagauzia and across Moldova.

Implement and Scale

Drought struck Moldova again in 2024, providing insight into how to structure a parametric solution for the Moldovan agriculture sector, including Gagauzia. The goal would be to provide predictable, high-velocity capital to farmers in need to meet their immediate economic security concerns and thus erode the effectiveness of foreign influence operations. So far, the Moldovan government has approved 100 million Moldovan lei ($5.74 million) to farmers for “whom the drought hit at least 60 percent of the harvest of maize and at least 70- [sic] percent of the harvest of wheat,” with a benefit per farmer of up to 500,000 lei ($28,700).

Immediately, this reads like a parametric insurance structure. There’s a maximum amount of protection available ($5.7 million) and a maximum benefit per farmer ($28,700). The 60% maize and 70% thresholds for qualifying for relief closely resemble crop-yield parametric triggers. This language suggests that structuring and implementing a parametric insurance program would not be difficult. Think back to the Istanbul example earlier in this article—the Moldovan government has already provided parameters and thresholds! The only work to remain would be to broaden the scope of what has been reported and secure donor premiums to finance a private insurance market purchase (which is the easy part).

Given that the structure would be insurance rather than aid, the $5.7 million allocated this year could be a lot more powerful as an insurance premium on a parametric policy, as it could lead to an overall amount of protection, potentially 5-10 times greater (or even more, depending on the structure). Further, given the relatively small amount of capital needed for premium, engaging donor states would become much easier, particularly given the leverage those donor states would enjoy relative to potential impact.

The cost of eroding the effectiveness of foreign influence in Moldova could be as low as $5.7 million. It’s an easy place to start.

More than Moldova

A policy recommendation to support Moldova does contemplate bringing some stability to a small state in a strategically important part of the world during intense upheaval. However, piloting a parametric insurance structure for Moldova’s agriculture sector should be seen as a first step toward a worldwide solution for stemming the tide of post-disaster foreign influence operations. The same thinking and approach applied to Moldova above is portable, as evidenced by the use of parametric insurance by governments in Latin America, the Caribbean, and parts of Africa. After testing in Moldova, success should lead swiftly to a much broader rollout. The economics of parametric insurance as a counter-influence tool are too compelling to ignore, and the ancillary benefits—feeding the victims of a natural disaster—only amplify the scale of the opportunity.

Using parametric insurance to counter foreign influence works best when several conditions are met. First, a state has to be exposed to natural disaster risk. It helps when that risk is easily measurable, but today, most are. Parametric solutions exist for wildfire, extreme heat, soil moisture, hail, and rainfall, alongside the more traditional tropical cyclone and earthquake perils. Next, priority should be given to communities most vulnerable to an influence campaign that can materially reshape the target population’s sentiment. While the United States may be large enough to absorb such efforts (although Hawaii is an alarming counterpoint), smaller countries with more delicate economies are not.

The scope of a parametric counter-influence program could easily begin with what Russian president Vladimir Putin has started to call the “World Majority,” which includes “Asian, Middle Eastern, African, and Latin American countries … [as] an unconditional priority of Russia’s foreign policy in the foreseeable future.” Unsurprisingly, this comes as anti-US and broader anti-western sentiment are on the rise in the region. That could change if the World Majority becomes a roadmap. If parametric insurance can provide a meal or two, maybe it will help keep the world out of chaos.

Tom Johansmeyer is a PhD candidate in international conflict analysis at the University of Kent, Canterbury. He is researching the cyber insurance protection gap as an economic security problem and is also a reinsurance broker in Bermuda, focusing on alternative forms of risk transfer in developing markets for emerging risks.

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official position of the Irregular Warfare Initiative, Princeton University’s Empirical Studies of Conflict Project, the Modern War Institute at West Point, or the United States Government.

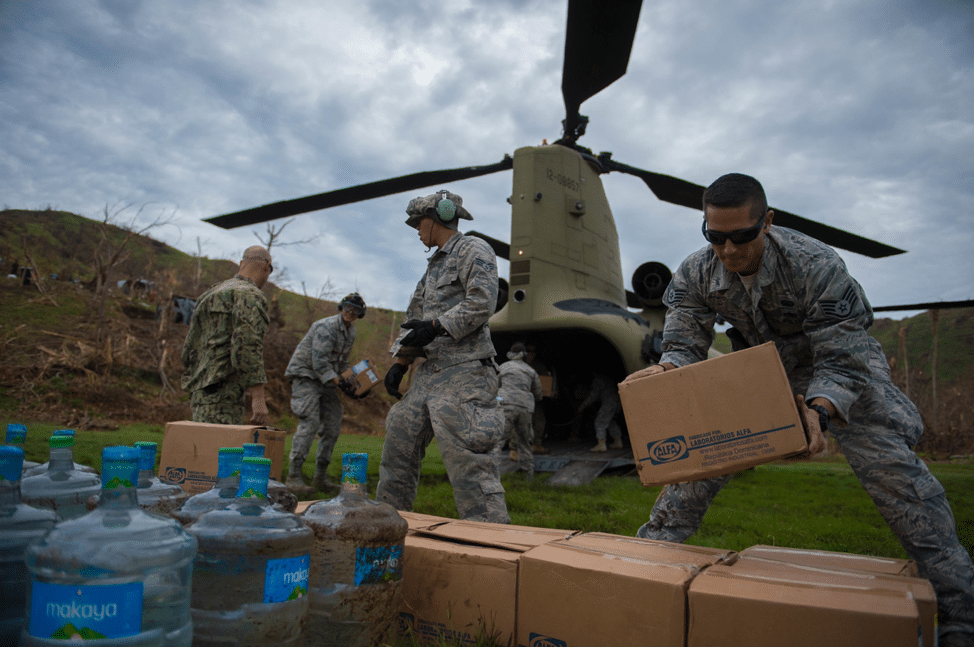

Main Image: US service members stack boxes of aid while off-loading a US Army CH-47 Chinook during an aid relief mission on October 14, 2016 in Anse d’Hainault, Haiti. (US Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Paul Labbe)

If you value reading the Irregular Warfare Initiative, please consider supporting our work. And for the best gear, check out the IWI store for mugs, coasters, apparel, and other items.

Leave a Reply